|

Journal

JOINTNESS’ IN

NATIONAL SECURITY PRIVATE PLANNING by Pankaj Joshi

In the last two years or so, and particularly after the Kargil

Review committee report was made public ‘jointness’ has become some

sort of a buzzword in the country’s strategic community. The

proponents feel that now that the value of jointness has begun to be

realised, there will be a sudden and dramatic change in our

strategic thinking. The detractors, on the other hand, feel that

this ‘new’ term is nothing but a load of western — and particularly

American — jargon and that we should not meddle with the things and

procedures, which have been in practice for many years and,

therefore, are time-tested. There are also doubts about what is

jointness and what exactly is it referring to. This article

discusses some of these issues. This article will not discuss in any

great detail such issues as national values, aims and interests and

such like except making a mention in passing because all of them are

irretrievably and irrevocably inter-linked. It will, however,

concentrate on the ‘elements of national power’ and see how

jointness in their development and optimum utilisation can impart

the nation a sense of security.

Before we proceed it is necessary to understand that in the

strategic sense jointness is not loss of speciality, everyone being

a jack-of-all-trades and master of none. It does not visualise

putting everyone in a uniform thinking mould. Indeed, the

multidisciplinary nature of national security makes such a thing

impossible. All it means is that various actors involved in national

security management cannot always act on their own without

consideration of the effect of their actions on other actors. Going

further, it implies that they should so plan and design their

actions so that not only do they accomplish their own purpose and

objective but also complement those of their fellow actors.

A clarification on the sense in which some of the terms are being

used would be in order.

The term ‘national security’ itself encompasses within itself two

separate concepts; that of ‘nation state’ and of ‘security.’ Without

getting into a debate on what constitutes a ‘nation,’ for the

purpose of this article we will assume that a people, residing

within a clearly defined geographical area, sharing a common past

and heritage, and having common aspirations and vision of the

future, constitute a nation state.

Similarly, any consideration of security also raises the questions

of security of ‘what’ and against what ‘threat.’ A systematic study

of the issues involved in the concept of security has been

undertaken only in recent times that. Perhaps the credit for

articulating in clear terms one view of national security could go

to Walter Lippman, an American analyst, who stated in 1943,

A nation is secure to the extent to which it is not in danger of

having to sacrifice core values if it wishes to avoid war, and is

able, if challenged, to maintain them by victory in case of war.

The emphasis in that definition is on ‘core values’ and ‘war,’

whether in its avoidance or in achieving victory in one, if one is

forced into it. However, with the end of the War and with many

erstwhile colonies becoming independent and having their own

political agendas, this definition, while still holding good to some

extent, was found to be too narrow. Jawaharlal Nehru, for example,

felt that :

For developing countries, security constitutes freedom from

economic, political and military threat to self-reliant development.

A more recent and omnibus definition, which takes into account the

fact that the threats today can manifest themselves in forms other

than purely military and that they need not necessarily be from

outside the state, is:

The ability of a nation to protect its internal values from external

threats, no matter in what form, or from what quarter they may

appear.

It needs to be noted that in this as well as in Lippman's

definition, the threat is to values and not something more concrete

and visible such as a part of a nation's territory, or its citizens,

or its trade. Of course, the threat to values can be translated in

to something more definite and defined in terms of territory and so

on. That is what definition of ‘national interests’ does. Indeed, so

close is the relation between ‘national values’ and ‘national

interests’ that they are often confused, one with the other. Lord

Palmerton’s quote of 1848 has now become almost a cliché and is

often quoted out of context and in many a distorted form. The

original and full quote is:

We have no eternal allies and we have no perpetual enemies. Our

interests are eternal and perpetual, and these interests it is our

duty to follow.

It is obvious that national interests emerge from the values that a

nation holds dear. Where ‘values’ may be somewhat vague and

philosophical in nature, ‘interests’ are more concrete and

practical. Also, whereas values may be unalterable, the interests

may at times have to be modified if they conflict with the

environment in which a nation is placed. Seen in this light

‘national interests’ may be defined as:

A country's perceived needs and aspirations in relation to other

sovereign states constituting its external environment.

As can be seen, this definition takes into account not only the

needs and aspirations of a particular country — as perceived by that

country — but also of those of other sovereign states. It implicitly

recognises that in modern world no country can isolate itself from

the rest and pursue its own national interests without taking into

account the interests of others.

If a nation were to define its national interests they could include

defence from external aggression, economic well being of our

citizens, international peace and security, promotion of values,

such as of democracy and secularism, and so on. One could add a few

more items to this, delete some of the items or alter their order;

essentially they are likely to remain the same. But what is more

important and interesting is that it could be argued that while

there may be a difference in nuance and the degree of importance

attached to one or the other, practically all nations will have

same or similar interests. to some extent there is validity in this

argument. That is why the emphasis on “…in relation to other

sovereign states constituting its external environment” given in the

last definition.

In order to effectively safeguard its interests a nation must have

power. National power, unlike values and interest discussed earlier,

is much more tangible and measurable. Yet it also consists of many

intangibles such as national will and morale. Also, it is tangible

only in the sense that because of certain visible manifestations of

state power, such as strong military and a buoyant economy, it is

possible to form a subjective opinion about whether a nation is

powerful or not. but it is very difficult to apply scientific and

objective methods to measure it in specific units of strength. Power

is difficult to define and scores of books have been written on

‘power.’ However, for a broad understanding in modern context is can

be defined as the ability to influence others’ behaviour.

Though different authors have different views on this, essentially

it is agreed that there are six elements of national power:

demography, geography, historical-psychological sociology,

politico-administrative organisation, economy, and military. These

are only the broadest categories; there could be many sub-divisions

of these. For example one could include natural resources, which

essentially are a function of geography. It is important to note

that

Demography refers not only to the size of the population but more to

its quality. A relatively small, literate and industrious population

may endow much greater power on a nation than a large, illiterate

and lethargic one could. Demography also includes such elements as

the technological manpower base and the scientific and strategic

temper of the population. The list is endless. It is in the context

of a ‘strategic temper’ that NISDA has been created and has an

important role to perform. Most Indians are generally ignorant about

issues pertaining to national security and are quite content to

leave such an important part of their well being in the hands of a

few self-appointed ‘experts.’

The geographic element of national power manifests itself not only

in the geographic location of a nation but also from the natural

resources that geography confers on it. A nation’s history, social

system and the psychological make up of the population have a

profound bearing on national power. Nations are seen or perceived to

be historically strong or weak; pacifists or belligerent; pessimists

or optimists. The political and administrative organisations

determine whether the national government will be stable or not. The

more stable the government and more the degree of consensus amongst

the people, the stronger will be a nation. It is important that the

three pillars of state, viz. the legislature, judiciary and the

executive be strong. In the modern world, increasingly a nation’s

scientific and technological base and capabilities determine its

power. In this context the amount spent on R & D and research

facilities provides a fairly good measure of capabilities. Here

again our record leaves much to be desired.

While all the above contribute towards making a nation strong, in

the final analysis, however, the economic and the military element

are the two most crucial, visible and measurable elements of

national power. Indeed, it can be said that it is the combined

effect of the other four, which gives a nation its economic

strength, which in turn allows it to build up its military strength.

One of the lessons of the break up of the erstwhile Soviet Union is

that no country, not even a super power, can be militarily strong

unless it is first economically strong. On the other hand, as can be

seen from the example of Japan, if a nation is prepared to trust its

security with some other nation, it can build itself up economically

without resorting to heavy military spending.

The economic power must be understood in its widest sense. It

includes such diverse fields as shipbuilding industry, the merchant

marine, warehousing and banking facilities. It includes road network

and transportation industry, railway network, and telecommunication

network. Indeed, there is hardly any field of human endeavour that

does not in one way or other contribute to a nation’s economic

strength. And that is why it is important that every citizen

realises that whatever his or her station in life and whatever the

field of activity, so long he or she is participating in some

economic activity he or she is contributing to the nation’s

security. It is the combined effort of the 999 million people of

this country that sustains the effort of the one odd million men and

women in uniform.

We now come to the question of, not so much the role, but the place

of the military in national security structure and policy

formulation. Clausewitzian theory about military being an instrument

of policy and war being continuation of policy by other means is

too well known to be repeated. In this formulation it is implied

that ‘other means’ have been tried and only on their not having

achieved the desired result, has war been resorted to. If this was

true in the nineteenth century it is much more so today, when many

are shunning war as an instrument of policy. It is this author’s

belief that one of the reasons for the traditional hostility between

the military and bureaucracy, not only in India but also in all

major democracies, has its roots in the difference in perception of

their respective roles in the national security structure. While the

military tends to consider its role to be the central one, the

politicians, diplomats and bureaucrats feel that if they have their

way and succeed the military will never have to be employed.

Therefore, the place of the military forces has to be seen in a

much larger context.

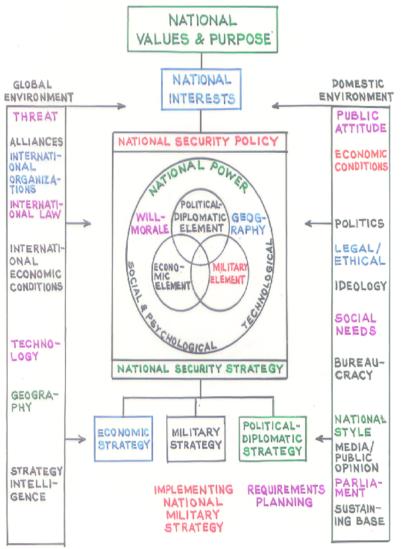

A schematic showing various elements that come into play in the

national security structure and how they impinge on each other is at

Appendix. It will be noticed that the military element forms only a

small cog in the total structure with a large number of other

diverse domestic and global factors also having a bearing on the

policy. Yet, as pointed out earlier, it is also one of the most

visible. It also has the aura of being the ‘court of last resort,’

as it were, since it actively comes into play when all else has been

tried and failed. (At times the military can play a ‘passive’ role

in conduct of policy when states may hold out a ‘threat’ of use of

military force to achieve their policy objectives). In either event

there can be no argument that the military force has to be credible.

Credibility of a force is not a function of its numerical strength

or weapons inventory alone. Similarly, training, motivation and

morale of the personnel, while being important cannot be termed the

crucial factors. In the final analysis the credibility of a military

force depends on the credibility of the political will.

Thus if a nation declares a certain objective to be a vital national

interest, it must back it up with adequate military power and must

have a demonstrated political will to use that force, if necessary.

Dr Michael Roskin, an American political scientist and analyst put

it very succinctly in a recent article when he said, “Always back

your interest with adequate power. If you don’t have the power,

don’t declare something distant to be your interest. Thou shalt not

bluff." I need only add an “Amen” to that quote!

This article would not be complete without a brief look at the

internal security situation, which forms a very important facet of

national security spectrum. Aid to civil authorities and maintenance

of law and order and internal security are amongst the roles of all

armies in democratic countries. However, it is implicit in such

employment that the committal of the armed forces would be for

absolutely minimum period and that the troops would be returned to

barracks at the earliest. Regrettably in India this has not happened

and the armed forces have been continuously deployed and committed

on internal security duties in Kashmir, Punjab, North East and

various other parts of the country.

Here it may be appropriate to cite the analogy of a sick person.

When a person becomes sick, in the beginning he is treated by his

family doctor, who generally treats the patient for symptoms. When

things get out of hand and the patient’s condition deteriorates, a

specialist is called in. He, in his own turn, carries out some more

tests and administers treatment, which is intensive – and expensive.

It may involve some surgery and blood letting. Having cured the

patient, the specialist withdraws, leaving the post-operative care

in the hands of the family doctor, who nurses the patient back to

good health. Substitute the patient with the body politic of a

state, the family doctor with the local police and law enforcement

agencies, and the specialist with the armed forces; and you have the

ideal prescription for handling insurgencies.

I will end this article with the final dénouement to show the role

of jointness lies in all these things. As is apparent, ‘national

security’ includes each and every facet of national life, including

its citizens’. In theory, therefore, each and every individual must

act in concert, one with the other, so that their combined energies

and their efforts result in making the nation strong. However, it is

equally obvious that practically it is impossible to achieve this.

But even if this cannot be done at the level of the individual, at

the level of the government is certainly is possible and must be

done. This is particularly so because all the activities involved

have long gestation periods of up to 15 to 20 years. Since

‘political will’ is central to it becomes important to have a broad

consensus amongst the political parties on the general direction

that the country is to take. Without such consensus, there cannot be

continuity in effort and the nation will move in the manner of a

rudderless ship. Whether it is the development of a particular

talent in human resource, or building a merchant marine,

infrastructure development, modernisation of armed forces, forging

diplomatic relations; all these must start and proceed to a plan.

Some body must give specific directions to the various agencies.

Their progress must be monitored, mid-course corrections applied,

someone asked to slow down while others may have to be exhorted to

hasten up. This is where ‘jointness’ is required. Obviously there

has to be a body or an agency, which does this job on a full-time

basis. And all this has to be done in a democratic manner with no

body treading on any body else’s turf. This appears a tall order,

but it can be done to a substantial degree.

In the final analysis, joint ness is nothing but joint thinking,

separate execution.

APPENDIX

|